Botanische Namen / Plant Names

| English Name | German Name | Botanic Name (Latin) |

|---|---|---|

| Fava bean | Ackerbohne | Vicia faba |

| Adzuki bean | Adzukibohne | Vigna angularis |

| Aloe vera | Aloe Vera | Aloe vera |

| Amaranth | Amaranth | Amaranthus |

| Pineapple | Ananas | Ananas comosus |

| Anise | Anis | Pimpinella anisum |

| Apple | Apfel | Malus domestica |

| Apricot | Aprikose | Prunus armeniaca |

| Artichoke | Artischocke | Cynara cardunculus var. scolymus |

| Eggplant | Aubergine | Solanum melongena |

| Avocado | Avocado | Persea americana |

| Banana | Banane | Musa |

| Basil | Basilikum | Ocimum basilicum |

| Wild garlic | Bärlauch | Allium ursinum |

| Bhut Jolkai (Pepper) | Bhut Jolkai | Capsicum chinense |

| Pear | Birne | Pyrus |

| Collard greens | Blattkohl | Brassica oleracea var. viridis |

| Blueberry | Blaubeere | Vaccinium corymbosum |

| Bell pepper | Blockpaprika | Capsicum annuum |

| Cauliflower | Blumenkohl | Brassica oleracea var. botrytis |

| Fenugreek | Bockshornklee | Trigonella foenum-graecum |

| Beans | Bohnen | Phaseolus vulgaris |

| Borage | Borretsch | Borago officinalis |

| Boysenberry | Boysenbeere | Rubus ursinus × idaeus |

| Feijoa | Brasilianische Guave | Acca sellowiana |

| Brown rice | Brauner Reis | Oryza sativa |

| Broccoli | Brokkoli | Brassica oleracea var. italica |

| Blackberry | Brombeere | Rubus fruticosus |

| Watercress | Brunnenkresse | Nasturtium officinale |

| Buckwheat | Buchweizen | Fagopyrum esculentum |

| Green bean | Buschbohne | Phaseolus vulgaris |

| Butternut squash | Butternut Kürbis | Cucurbita moschata |

| Cantaloupe melon | Cantaloupe Melone | Cucumis melo var. cantalupensis |

| Cardoon | Cardy | Cynara cardunculus |

| Chayote | Chayote | Sechium edule |

| Chia | Chia | Salvia hispanica |

| Chicory | Chicoree | Cichorium intybus |

| Chili pepper | Chili | Capsicum |

| Napa cabbage | Chinakohl | Brassica rapa subsp. pekinensis |

| Chinese sumac | Chinesischer Surenbaum | Toxicodendron vernicifluum |

| Cranberry | Cranberry | Vaccinium oxycoccos |

| Daikon radish | Daikon | Raphanus sativus var. longipinnatus |

| Dill | Dill | Anethum graveolens |

| Spelt | Dinkel | Triticum spelta |

| Dragon fruit | Drachenfrucht | Hylocereus undatus |

| St. John's wort | Echtes Johanniskraut | Hypericum perforatum |

| Chestnut | Edelkastanie | Castanea sativa |

| Acorn squash | Eichelkürbis | Cucurbita pepo var. turbinata |

| Iceberg lettuce | Eisbergsalat | Lactuca sativa var. capitata |

| Endive | Endivie | Cichorium endivia |

| Angelica | Engelwurz | Angelica archangelica |

| Beans (Pepper) | Erbse | Pisum sativum |

| Strawberry | Erdbeere | Fragaria × ananassa |

| Peanut | Erdnuss | Arachis hypogaea |

| Edible flower | Essbare Blume | Various |

| Pickled cucumber | Essiggurke | Cucumis sativus |

| Tarragon | Estragon | Artemisia dracunculus |

| Corn salad | Feldsalat | Valerianella locusta |

| Fig | Feige | Ficus carica |

| Corn salad | Feldsalat | Valerianella locusta |

| Fennel | Fenchel | Foeniculum vulgare |

| Fire bean | Feuerbohne | Phaseolus coccineus |

| Bottle gourd | Flaschenkürbis | Lagenaria siceraria |

| Tarragon | Französischer Estragon | Artemisia dracunculus |

| Lentils | Französische Linsen | Lens culinaris |

| Gem squash | Gem Squash | Cucurbita pepo |

| Tree spinach | Gartenmelde | Atriplex hortensis |

| Barley | Gerste | Hordeum vulgare |

| Green bean | Grüne Bohne | Phaseolus vulgaris |

| Green pea | Grüne Erbse | Pisum sativum |

| Kale | Grünkohl | Brassica oleracea var. sabellica |

| Cucumber | Gurke | Cucumis sativus |

| Oats | Hafer | Avena sativa |

| Hemp | Hanf | Cannabis sativa |

| Raspberry | Himbeere | Rubus idaeus |

| Millet | Hirse | Panicum miliaceum |

| Passion fruit | Indianerbanane | Passiflora edulis |

| Ginger | Ingwer | Zingiber officinale |

| Blackcurrant | Johannisbeere | Ribes nigrum |

| Chamomile | Kamille | Matricaria chamomilla |

| Nasturtium | Kapuzienerkresse | Tropaeolum majus |

| Carrot | Karotte | Daucus carota subsp. sativus |

| Potato | Kartoffel | Solanum tuberosum |

| Catnip | Katzenminze | Nepeta cataria |

| Chervil | Kerbel | Anthriscus cerefolium |

| Chickpea | Kichererbse | Cicer arietinum |

| Kidney bean | Kidney Bohne | Phaseolus vulgaris |

| Clover | Klee | Trifolium |

| Garlic | Knoblauch | Allium sativum |

| Celeriac | Knollensellerie | Apium graveolens var. rapaceum |

| Cabbage | Kohl | Brassica oleracea |

| Kohlrabi | Kohlrabi | Brassica oleracea var. gongylodes |

| Japanese mustard spinach | Komatsuna | Brassica rapa var. perviridis |

| Cabbage | Kopfkohl | Brassica oleracea var. capitata |

| Head lettuce | Kopfsalat | Lactuca sativa |

| Cilantro | Koriander | Coriandrum sativum |

| Cress | Kresse | Lepidium sativum |

| Pumpkin | Kürbis | Cucurbita pepo |

| Cilantro | Langer Koriander | Eryngium foetidum |

| Leek (Summer) | Lauch (Sommer) | Allium ampeloprasum var. porrum |

| Leek (Winter) | Lauch (Winter) | Allium ampeloprasum var. porrum |

| Lavender | Lavendel | Lavandula |

| Flaxseed | Leinsamen | Linum usitatissimum |

| Lovage | Liebstöckel | Levisticum officinale |

| Lentil | Linse | Lens culinaris |

| Dandelion | Löwenzahn | Taraxacum |

| Alfalfa | Luzerne | Medicago sativa |

| Corn | Mais | Zea mays |

| Marjoram | Majoran | Origanum majorana |

| Marjoram | Majoran | Origanum vulgare |

| Almond | Mandeln | Prunus dulcis |

| Swiss chard | Mangold | Beta vulgaris subsp. vulgaris var. flavescens |

| Horseradish | Meerrettich | Armoracia rusticana |

| Cherry | Melone | Prunus avium |

| Mint | Minze | Mentha |

| Mizuna | Mizuna | Brassica rapa var. nipposinica |

| Carrot | Möhre | Daucus carota subsp. sativus |

| Mung bean | Mungobohne | Vigna radiata |

| Okra | Okra | Abelmoschus esculentus |

| Oregano | Oregano | Origanum vulgare |

| Pak Choi | Pak Choi/Tatsui | Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis |

| Papaya | Papau/Pawpaw | Carica papaya |

| Bell pepper | Paprika | Capsicum annuum |

| Passion fruit | Passionsfrucht | Passiflora edulis |

| Parsnip | Pastinake | Pastinaca sativa |

| Patison | Patison | Cucurbita pepo var. patisson |

| Pepino | Pepino/Peperoni | Solanum muricatum |

| Persimmon | Persimmon | Diospyros kaki |

| Parsley | Petersilie | Petroselinum crispum |

| Pepper | Pfeffer | Piper nigrum |

| Peppermint | Pfefferminze | Mentha × piperita |

| Peach | Pfirsich | Prunus persica |

| Plum | Pflaume | Prunus domestica |

| Foot | Pfote | Various |

| Purslane | Portulak | Portulaca oleracea |

| Quinoa | Quinoa | Chenopodium quinoa |

| Radish | Radicchio | Cichorium intybus |

| Radish | Radieschen | Raphanus sativus |

| Radish (China Rose) | Radieschen China Rose | Raphanus sativus var. sativus |

| Radish (Scarlet Globe) | Radieschen Scarlet Globe | Raphanus sativus |

| Arugula | Rakete | Eruca sativa |

| Rapeseed | Raps | Brassica napus |

| Raspberry | Himbeere | Rubus idaeus |

| Rock Melon | Rock Melone | Cucumis melo |

| Rhubarb | Rhabarber | Rheum rhabarbarum |

| Wild garlic | Rosmarin | Allium ursinum |

| Rosemary | Rosmarin | Salvia rosmarinus |

| Red cabbage | Rotkohl | Brassica oleracea var. capitata f. rubra |

| Radish | Rübe | Raphanus sativus |

| Red radish | Rübli | Daucus carota subsp. sativus |

| Rucola | Rucola | Eruca sativa |

| Spinach | Spinat | Spinacia oleracea |

| Chard | Stängelkohl | Beta vulgaris subsp. vulgaris var. cicla |

| Samphire | Schwadenzunge | Crithmum maritimum |

| Shallot | Schalotte | Allium cepa var. aggregatum |

| Black salsify | Scorzonera | Scorzonera hispanica |

| Seakale | Meerrettich | Crambe maritima |

| Yellow pepper | Gelbe Paprika | Capsicum annuum |

| Sesame | Sesam | Sesamum indicum |

| Shiitake | Shiitake | Lentinula edodes |

| Savoy cabbage | Savoyen | Brassica oleracea var. sabauda |

| Sorrel | Sauerampfer | Rumex acetosa |

| Soybean | Soja | Glycine max |

| Black salsify | Scorzonera | Scorzonera hispanica |

| Wild garlic | Schnittknoblauch | Allium tuberosum |

| Purple sprouting broccoli | Spargelbrokkoli | Brassica oleracea var. italica |

| Spinach | Spinat | Spinacia oleracea |

| Squash | Squash | Cucurbita pepo |

| Squash (Acorn) | Squash (Eichelkürbis) | Cucurbita pepo var. turbinata |

| Squash (Butternut) | Squash (Butternut-Kürbis) | Cucurbita moschata |

| Squash (Hokkaido) | Squash (Hokkaido) | Cucurbita maxima |

| Squash (Pumpkin) | Squash (Kürbis) | Cucurbita pepo |

| Red cabbage | Rotkohl | Brassica oleracea var. capitata f. rubra |

| Sweet potato | Süßkartoffel | Ipomoea batatas |

| Celery | Staudensellerie | Apium graveolens |

| Asparagus | Spargel | Asparagus officinalis |

| Spinach | Spinat | Spinacia oleracea |

| Strawberry | Erdbeere | Fragaria × ananassa |

| Tomato | Tomate | Solanum lycopersicum |

| Tomatillo | Tomatillo | Physalis philadelphica |

| Thyme | Thymian | Thymus |

| Tarwi | Tarwi | Lupinus mutabilis |

| Turnip | Rübe | Brassica rapa subsp. rapa |

| Cherry tomato | Kirschtomate | Solanum lycopersicum var. cerasiforme |

| Tomato | Paradeiser | Solanum lycopersicum |

| Watercress | Wasserkresse | Nasturtium officinale |

| Watermelon | Wassermelone | Citrullus lanatus |

| Water spinach | Wasserspinat | Ipomoea aquatica |

| Water chestnut | Wasserkastanie | Trapa natans |

| White radish | Weißer Rettich | Raphanus sativus |

| White cabbage | Weißkohl | Brassica oleracea var. capitata |

| White mustard | Weißer Senf | Sinapis alba |

| White mustard | Weißer Senf | Sinapis alba |

| Wasabi | Wasabi | Wasabia japonica |

| Wheat | Weizen | Triticum |

| Zucchini | Zucchini | Cucurbita pepo |

- Category: Biologie

This article is about the bacteria (communities) that a biofilter requires in order to be able to reintroduce the fish excretions into the food cycle in an aquaponics system or in aquaculture. The necessary balance in the bacterial community is fragile and extremely complex. In the following compilation of scientific research results you will find studies about the biofilters (compositions) used in aquaponics and their interaction both with each other and with their environment.

This article contains, among other things, excerpts and translations from studies by the School of Freshwater Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, USA. Authors and information about the sources used can be found at the end of this article . We assume no liability for the accuracy of the translation or the scientific statements or the conclusions drawn from them. According to fisheries experts from LANUV and the ministry, practical experience shows that new systems only produce around 10% - 30% of the maximum possible biomass in the first few years. In stable operation, recirculation systems are operated at approx. 70% - 80% of their capacity.

Recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) are unique engineered ecosystems that minimize environmental disturbances by reducing the discharge of nutrient pollution. RAS typically use a biofilter to control ammonia levels, which are a byproduct of fish protein breakdown.

Nitrosomonas (ammonia oxidizing), Nitrospira , and Nitrobacter (nitrite oxidizing) species are believed to be the primary nitrifiers present in RAS biofilters. We examined this claim by characterizing the biofilter bacterial and archaeal community of a commercial-scale freshwater RAS that has been in operation for >15 years. We found that the biofilter community harbored a diverse range of bacterial taxa (>1000 taxon assignments at the genus level), dominated by Chitinophagaceae (~12%) and Acidobacteria (~9%). The bacterial community showed significant shifts in composition with changes in biofilter depth and associated with operational changes over a fish rearing cycle. Archaea were also abundant and consisted exclusively of a low diversity (>95%) assemblage of Thaumarchaeota , which were considered ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) due to the presence of AOA ammonia monooxygenase genes. Nitrosomonas were present at all depths and at all times. However, their abundance was >3 orders of magnitude lower than AOA and showed significant depth-time variability not observed in AOA. Phylogenetic analysis of the nitrite oxidoreductase beta subunit ( nxrB ) gene showed two distinct Nitrospira populations were present, while Nitrobacter were not detected. Subsequent identification of Nitrospira ammonia monooxygenase alpha subunit genes coupled with phylogenetic placement and quantification of nxrB genotypes suggests that complete ammonia-oxidizing (comammox) and nitrite-oxidizing Nitrospira populations exist in this system with relatively equivalent and stable frequencies coexist. It appears that RAS biofilters harbor complex microbial communities whose composition can be directly influenced by typical system operation, while supporting multiple ammonia oxidation lifestyles within the nitrifying consortium.

The development of aquaculture technology allows societies to reduce dependence on capture fisheries and offset the effects of declining fish stocks ( Barange et al., 2014 ). Aquaculture production now accounts for almost 50% of fish produced for consumption, and it is estimated that a fivefold increase in production will be required over the next two decades to meet societal protein needs (FAO, 2014 ) . However, expanding production will increase the environmental impact of aquaculture facilities and raises important concerns about the sustainability of aquaculture practices. Recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) were developed to overcome pollution problems and storage capacity limitations of conventional terrestrial aquaculture facilities ( Chen et al., 2006 ; Martins et al., 2010 ). RAS offer several advantages over traditional flow-through systems, including: 90–99% less water consumption ( Verdegem et al., 2006 ; Badiola et al., 2012 ), more efficient waste management ( Piedrahita, 2003 ), and potential for implementation at sites requiring distance to the market ( Martins et al., 2010 ). RAS components are similar to those used in wastewater treatment, including solids separation and nitrogenous waste removal from excess animal waste and undigested feed. The advancement of RAS technology and advantages over flow-through systems have led to increasing use of RAS, particularly in countries that place great emphasis on minimizing environmental impacts ( Badiola et al., 2012 ) and in urban areas where space is limited is ( Klinger and Naylor, 2012 ).

Nitrifying biofilters are a critical component of most RAS and an important factor in operational success. These biofilters are also cited as the biggest hurdle to RAS commissioning and the most difficult component to manage once the RAS is operational ( Badiola et al., 2012 ). RAS biofilters are designed to remove nitrogenous waste byproducts created by fish protein catabolism and oxidation processes. Ammonia and nitrite are of utmost importance to freshwater aquaculturists because the toxic dose of both types of nitrogen depends on the pH and the aquatic organism being reared ( Lewis and Morris, 1986 ; Randall and Tsui, 2002 ). In RAS engineering, designers typically refer to the major nitrifying taxa as Nitrosomonas spp. (ammonia oxidizers) and Nitrobacter spp. (nitrite oxidizers) ( Kuhn et al., 2010 ) and model system capacity from the physiologies of these organisms ( Timmons and Ebeling, 2013 ). It is now clear that Nitrosomonas and Nitrobacter are typically absent or present at low levels in freshwater nitrifying biofilters ( Hovanec and DeLong, 1996 ), while Nitrospira spp. are common ( Hovanec et al., 1998 ). Recent studies of biofilters in freshwater aquaculture have expanded the nitrifying taxa present in these systems to include ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA), a variety of Nitrospira spp. and Nitrotoga expanded ( Sauder et al., 2011 ; Bagchi et al., 2014 ; Hüpeden et al., 2016 ). Further studies are required to understand whether other nitrifying consortia RAS biofilters together with Nitrosomonas and Nitrobacter spp. inhabit or whether diverse collections of nitrifying organisms are characteristic of highly functional systems. A more refined understanding of the physiology of RAS biofilter nitrification consortia would inform system design optimization and could change parameters now considered design constraints.

The non-nitrifying component of RAS biofilter communities also influences biofilter function. Heterotrophic biofilm overgrowth can limit oxygen availability to the autotrophic nitrifying community, resulting in reduced ammonia oxidation rates ( Okabe et al., 1995 ). Conversely, optimal heterotrophic biofilm formation protects the slower growing autotrophs from biofilm shear stress and recycles autotrophic biomass ( Kindaichi et al., 2004 ). Previous studies have shown that the diversity of non-nitrifying microorganisms in RAS biofilters could be high and could sometimes contain opportunistic pathogens and other commercially harmful organisms ( Schreier et al., 2010 ). However, most of these studies used low-coverage characterization methods (e.g. DGGE, clone libraries) to describe the taxa present, so the extent of this diversity and similarity between systems is relatively unknown. Recently, the bacterial community of a series of seawater RAS biofilters operated at different salinity and temperature combinations was characterized using massively parallel sequencing technology ( Lee et al., 2016 ). This study provided the first in-depth examination of a RAS biofilter microbial community, revealing a highly diverse bacterial community that changed in response to environmental conditions, but a more consistent nitrifying assemblage typically dominated by microorganisms of the Nitrospira classification .

In this study, we aimed to characterize in depth the bacterial and archaeal community structure of a commercial freshwater RAS culture of Perca flavescens (yellow perch) using a vortex sand biofilter that has been in operation for more than 15 years. We hypothesized that the biofilter sand biofilm community would exhibit temporal variability associated with environmental changes associated with the animal rearing process and diverse nitrifying assemblage. To answer these questions, we used massively parallel sequencing to characterize the bacterial and archaeal biofilter community across depth and time gradients. We also identified and phylogenetically classified nitrification marker genes for the alpha subunit of ammonia monooxygenase ( amoA ; Rotthauwe et al., 1997) ; Pester et al., 2012 ; van Kessel et al., 2015 ) and nitrite oxidoreductase alpha ( nxrA ; Poly et al., 2008 ; Wertz et al., 2008 ) and beta ( nxrB ; Pester et al., 2014 ) subunits present in the biofilter, and then tracks their frequency with biofilter depth and over the course of a fish rearing cycle.

Materials and methods

Description of the UWM biofilter

All samples were collected by the RAS biofilter (UWM biofilter) at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Great Lakes Aquaculture Facility. Measured from the base, the biofilter is ~2.74 m high and ~1.83 m in diameter. The water level within the biofilter is ~2.64 m from the base, with the fluidized sand filter matrix extending to a height of Extends ~1.73 m from the base. The biofilter is filled with Wedron 510 silica sand, which is fluidized to ~200% starting sand volume through the use of 19 Plan 40 PVC probes, each 3.175 cm in diameter. The probes receive inflow from the solid waste clarifier, which rises through the filter matrix. Samples for this study were collected at three depths within the fluidized sand biofilter, defined as surface (~1.32–1.42 m from the biofilter base), middle (~0.81–0.91 m from the biofilter base), and bottom (~0.15–0.30 m, made from biofilter base). Images of the UWM biofilter and sampling locations are shown in Figure 1 . The maximum flow rate of the biofilter inflow is 757 L per minute, resulting in a hydraulic retention time of ~9.52 min. Typical system water quality parameters are as follows (mean ± standard deviation): pH 7.01 ± 0.09, oxidation-reduction potential 540 ± 50 (mV), water temperature 21.7 ± 0.9 (°C), and dissolved oxygen (DO) of biofilter effluent 8.20 ± 0.18 mg/l. The biofilter is designed for maximum operation at 10 kg of feed per day, which is based on predicted ammonia production from fish protein breakdown at this feeding rate ( Timmons and Ebeling, 2013 ).

Sample collection, processing and DNA extraction

Samples from the top of the biofilter matrix were collected in autoclaved 500 mL polypropylene bottles. Two samples from the surface of the biofilter were collected during the last 2 months of a yellow perch rearing cycle and then immediately before the start of a new rearing cycle in the system. After the system was stocked with fish, samples were collected approximately every week for the first half of the new rearing cycle (the yellow perch strains present during this study take approximately 9 months to grow to market size). After collection, water from the biofilter matrix samples was decanted into a second sterile 500 mL bottle for further processing. Then, approximately 1 g of wet weight sand was removed from the sample bottle and frozen at −80 °C for storage prior to DNA extraction. Water samples were filtered to 0. 22 μm filters (47 mm mixed cellulose esters, EMD Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) frozen at −80 °C and macerated with a sterilized spatula before DNA extraction. To address the spatial distribution of bacterial taxa separately, depth samples were collected from the filter matrix using 50 ml syringes with attached weighted Tygon tubing (3.2 mm ID, 6.4 mm OD; Saint-Gobain SA, La Défense, Courbevoie , France). Samples were categorized according to the approximate distance from the filter base as surface, center, and bottom. The tubing was sterilized with 10% bleach and rinsed three times with sterile deionized water between samplings. DNA was extracted separately from biofilter sand and water samples (~1 g wet weight and 100 mL, respectively) using the MP Bio FastDNA and macerated with a sterilized spatula before DNA extraction. To address the spatial distribution of bacterial taxa separately, depth samples were collected from the filter matrix using 50 ml syringes with attached weighted Tygon tubing (3.2 mm ID, 6.4 mm OD; Saint-Gobain SA, La Défense, Courbevoie , France). Samples were categorized according to the approximate distance from the filter base as surface, center, and bottom. The tubing was sterilized with 10% bleach and rinsed three times with sterile deionized water between samplings. DNA was extracted separately from biofilter sand and water samples (~1 g wet weight and 100 mL, respectively) using the MP Bio FastDNA and macerated with a sterilized spatula before DNA extraction. To address the spatial distribution of bacterial taxa separately, depth samples were collected from the filter matrix using 50 ml syringes with attached weighted Tygon tubing (3.2 mm ID, 6.4 mm OD; Saint-Gobain SA, La Défense, Courbevoie , France). Samples were categorized according to the approximate distance from the filter base as surface, center, and bottom. The tubing was sterilized with 10% bleach and rinsed three times with sterile deionized water between samplings. DNA was extracted separately from biofilter sand and water samples (~1 g wet weight and 100 mL, respectively) using the MP Bio FastDNA. Depth samples were extracted from the filter matrix using 50 mL syringes with attached weighted Tygon tubing (3.2 mm ID, 6.4 mm OD; Saint-Gobain SA, La Défense, Courbevoie, France). Samples were categorized according to the approximate distance from the filter base as surface, center, and bottom. The tubing was sterilized with 10% bleach and rinsed three times with sterile deionized water between samplings. DNA was extracted separately from biofilter sand and water samples (~1 g wet weight and 100 mL, respectively) using the MP Bio FastDNA. Depth samples were extracted from the filter matrix using 50 mL syringes with attached weighted Tygon tubing (3.2 mm ID, 6.4 mm OD; Saint-Gobain SA, La Défense, Courbevoie, France). Samples were categorized according to the approximate distance from the filter base as surface, center, and bottom. The tubing was sterilized with 10% bleach and rinsed three times with sterile deionized water between samplings. DNA was extracted separately from biofilter sand and water samples (~1 g wet weight and 100 mL, respectively) using the MP Bio FastDNA. The tubing was sterilized with 10% bleach and rinsed three times with sterile deionized water between samplings. DNA was extracted separately from biofilter sand and water samples (~1 g wet weight and 100 mL, respectively) using the MP Bio FastDNA. The tubing was sterilized with 10% bleach and rinsed three times with sterile deionized water between samplings. DNA was extracted separately from biofilter sand and water samples (~1 g wet weight and 100 mL, respectively) using the MP Bio FastDNA 4mm OD; Saint-Gobain SA, La Défense, Courbevoie, France). Samples were categorized according to the approximate distance from the filter base as surface, center, and bottom. The tubing was sterilized with 10% bleach and rinsed three times with sterile deionized water between samplings. DNA was extracted separately from biofilter sand and water samples (~1 g wet weight and 100 mL, respectively) using the MP Bio FastDNA. The tubing was sterilized with 10% bleach and rinsed three times with sterile deionized water between samplings. DNA was extracted separately from biofilter sand and water samples (~1 g wet weight and 100 mL, respectively) using the MP Bio FastDNA. The tubing was sterilized with 10% bleach and rinsed three times with sterile deionized water between samplings. DNA was extracted separately from biofilter sand and water samples (~1 g wet weight and 100 mL, respectively) using the MP Bio FastDNA 4mm OD; Saint-Gobain SA, La Défense, Courbevoie, France). Samples were categorized according to the approximate distance from the filter base as surface, center, and bottom. The tubing was sterilized with 10% bleach and rinsed three times with sterile deionized water between samplings. DNA was extracted separately from biofilter sand and water samples (~1 g wet weight and 100 mL, respectively) using the MP Bio FastDNA. The tubing was sterilized with 10% bleach and rinsed three times with sterile deionized water between samplings. DNA was extracted separately from biofilter sand and water samples (~1 g wet weight and 100 mL, respectively) using the MP Bio FastDNA. The tubing was sterilized with 10% bleach and rinsed three times with sterile deionized water between samplings. DNA was extracted separately from biofilter sand and water samples (~1 g wet weight and 100 mL, respectively) using the MP Bio FastDNA® SPIN Kit for Soil (MP Bio, Solon, OH, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions, except that each sample was beaten for 2 minutes with the beads included in the MP Bio FastDNA ® SPIN Kit at the single operating speed of the Mini-BeadBeater - 16 (Biospec Products, Inc., Bartlesville, OK, USA). DNA quality and concentration were checked using a NanoDrop ® Lite (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Sample details and associated environmental data and molecular analyzes are presented in Table S1.

Ammonia and nitrite measurements

For both the time series and depth profiles, a Seal Analytical AA3 Autoanalyzer (Seal Analytical Inc., Mequon, WI, USA) was used to quantify ammonia and nitrite using the manufacturer-supplied phenol and sulfanilamide protocols on two separate channels became. To quantify nitrite only, the cadmium reduction column was not installed in the Auto Analyzer. RAS operators recorded all other chemical parameters from submerged probes that measured temperature, pH and oxidation-reduction potential. Following laboratory standard operating procedures, RAS operators used Hach colorimetric kits to measure ammonia and nitrite concentrations in the rearing tank.

16S rRNA gene sequencing

To maximize read depth for a temporal study of biofilter surface communities, we used the Illumina HiSeq platform and separately targeted the V6 region of the 16S rRNA gene for archaea and bacteria . In total, we received community data from 15 dates for temporal analysis. To interrogate changes in the spatial distribution of taxa across depth in the biofilter and obtain increased taxonomic resolution, we used 16S rRNA gene V4-V5 region sequencing on an Illumina MiSeq. We obtained samples from three depths n = 5 for the surface, n = 5 for the middle and n = 4 for the bottom. Example metadata is listed in Table S1. Extracted DNA samples were sent to the Josephine Bay Paul Center at the Marine Biological Laboratory (V6 Archaea and V6 Bacteria ; V4-V5 samples from 12/8/2014 to 2/18/2015) and to the Great Lakes Genomic Center (V4-V5 samples from 11/18 .2014, 12/2/2014, 12/18/2014) for massively parallel 16S rRNA gene sequencing using previously published bacterial ( Eren et al., 2013 ) and archaeal ( Meyer et al., 2013 ) V6 Illumina HiSeq and bacterial V4 V5 Illumina MiSeq chemistry ( Huse et al., 2014b ; Nelson et al., 2014 ). Reaction conditions and primers for all Illumina runs are listed in the citations above and can be accessed at: https://vamps.mbl.edu/resources/primers.php#illumina. Sequence run processing and quality control for the V6 data set are in Fisher et al. (2015) , while CutAdapt was used to trim the V4-V5 data from low quality nucleotides (phred score <20) and primers ( Martin, 2011 ; Fisher et al., 2015 ). Trimmed reads were merged using Illumina Utils as described previously ( Newton et al., 2015 ). Minimum Entropy Decomposition (MED) was implemented for each dataset to group sequences (MED nodes = operational taxonomic units, OTUs) for sample community composition and diversity analysis ( Eren et al., 2015 ). MED uses the information uncertainty calculated via Shannon entropy at all nucleotide positions of an alignment to divide sequences into sequence-like groups ( Eren et al., 2015 ). The sequence datasets were parsed with the following minimum substantial abundance settings: Bacteria V6, 377; archaeal V6, 123; bacterial V4-V5, 21. The minimum substantial threshold sets the abundance threshold for inclusion of MED nodes (i.e. OTU) in the final data set. Minimum substantial frequencies were calculated by dividing the total number of 16S rRNA gene sequences per data set by 50,000 as suggested in MED Best Practices (sequence counts are listed in Table S2). The Global Alignment for Sequence Taxonomy (GAST) algorithm was used to assign a taxonomy to sequence reads ( Huse et al., 2008 ) and the Visualization and Analysis of Microbial Population Structures (VAMPS; Huse et al., 2014a ) website was used for uses data visualization.

Comammox -amoA- PCR

To target comammox Nitrospira amoA for PCR and subsequent cloning and sequencing, amoA nucleotide sequences were obtained from van Kessel et al. (2015) and Daims et al. (2015) were aligned with MUSCLE ( Edgar, 2004 ). The alignment was imported into EMBOSS to generate an amoA consensus sequence ( Rice et al., 2000 ). Primer sequences were identified from consensus using Primer3Plus (Untergasser et al., 2012) , and the candidates along with those described by van Kessel et al. (2015), were evaluated from the consensus sequence in SeqMan Pro (DNAStar) using MUSCLE ( Edgar, 2004 ). The pmoA forward primer ( Luesken et al., 2011 ) and the candidate primer COM_amoA_1R (this study; Table 1 ) provided the best combination of read length and specificity and were subsequently used to amplify amoA genes from our samples.

Construction of a clone library and phylogenetic analysis

Multiple endpoint PCR approaches were used to examine the nitrifying community composition of the RAS fluidized sand biofilter for amoA ( Gammaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, Archaea, and Comammox Nitrospira ), nxrA ( Nitrobacter spp.), and nxrB (Non- Nitrobacter NOB). The primer sets and reaction conditions used are listed in Table 1 . All endpoint PCR reactions were performed with a volume of 25 μl: 12.5 μl 2x Qiagen PCR master mix (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), 1.5 μl appropriate primer mix (F&R), 0.5 μl bovine serum albumin ( BSA), 0.75 μl 50 mM MgCl 2 and 1 μl DNA extract.

DNA samples of biofilter water and sand from four different time points of the rearing cycle were used to create clone libraries of archaeal amoA and Nitrospira sp. nxrB . A sample from the middle of the sand biofilter was used to construct clone libraries for Betaproteobacteria -amoA and Comammox -amoA . The middle biofilter sample was selected because it produced well-defined amplicons suitable for cloning target amoA genes. All PCR reactions for cloning libraries were constructed using a TOPO-PCR 2.1 TA cloning kit plasmid (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Libraries were sequenced on an ABI 3730 Sanger sequencer with M13 forward primers. Vector plasmid sequence contamination was removed using DNAStar (Lasergene Software, Madison, WI).

Cloned sequences of Betaproteobacteria amoA, Archaea amoA, and Nitrospira nxrB from this study were added to ARB alignment databases from previous studies ( Abell et al., 2012 ; Pester et al., 2012 , 2014 ). Comammox -amoA sequences from this study were compared with those from van Kessel et al. matched. (2015) , Pinto et al. (2015) and Daims et al. (2015) using MUSCLE and imported into a new ARB database where the alignment was heuristically corrected prior to phylogenetic tree reconstruction. For the AOA, AOB and Nitrospira amoA phylogenies, relationships were determined using maximum likelihood (ML) with RAxML on the Cipres Science Gateway ( Miller et al., 2010 ; Stamatakis, 2014 ) and Bayesian inference (BI). calculated by MrBayes with a significant posterior probability of <0.01 and the associated consensus tree ( Abell et al., 2012 ; Pester et al., 2012 , 2014 ) integrated by ARB into a tree block within the input nexus file to reduce the calculation time ( Miller et al., 2010 ; Ronquist et al., 2012 ). Consensus trees were then calculated from the ML and BI reconstructions using ARB's consensus tree algorithm ( Ludwig et al., 2004 ).

The Nitrospira nxrB sequences generated in this study were significantly shorter than those used for the nxrB phylogenetic reconstruction in Pester et al. (2014) , therefore we did not perform phylogenetic reconstructions as with the other marker genes. Instead, the UWM Biofilter and Candidatus Nitrospira nitrificans sequences were added to the majority consensus tree by Pester et al. (2014) using the quick-add parsimony tool of the ARB package ( Ludwig et al., 2004 ). This tool uses sequence similarity to add sequences to pre-existing trees without changing the tree topology.

qPCR assays for target marker genes

Quantitative PCR assays were developed to distinguish two Nitrospira nxrB genotypes and two Nitrosomonas amoA genotypes in our system. Potential qPCR primer sequences were identified using Primer3Plus ( Untergasser et al., 2012 ) on MUSCLE ( Edgar, 2004 ) generated alignments in DNAStar (Lasergene Software, Madison, WI). Primer concentrations and annealing temperatures were optimized for specificity for each reaction target. Primers were checked using Primer-BLAST on NCBI to ensure assays matched their target genes. The newly designed primers were tested for cross-reactivity between genotypes using the non-target genotype sequence in both endpoint and real-time PCR dilution series. After optimization, all assays amplified only the target genotype. Due to the high sequence similarity between the two archaeal amoA genotypes (>90% identity) in our system, a single qPCR assay was developed to target both genotypes using the steps described above. The two closely related sequence types were pooled in equimolar amounts for reaction standards. A Komammox amoA qPCR primer set was developed using the same methods as the other assays presented in this study. All test conditions are listed in Table 1 . All qPCR assays were performed on an Applied Biosystems StepOne Plus thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Cloned target genes were used to generate standard curves from 1.5 × 10 6 to 15 copies per reaction. All reactions were performed in triplicate, with melting curve and endpoint confirmation of the assays (qPCR standard curve parameters and efficiency are listed in Table S3).

Statistics and data analysis

Taxonomy-based data were visualized with heatmaps created in the R statistical language ( R Core Team, 2014 ) by implementing functions from the gplots, Heatplus from Bioconductor Lite, VEGAN, and RColorBrewer libraries. MED nodes were used in all sample diversity metrics. The EnvFit function in the VEGAN ( Oksanen et al., 2015 ) R package was used to test the relationship between RAS observation data and changes in biofilter bacterial community composition. Pearson's correlations were calculated using the Hmisc package in R ( Harrell, 2016 ) to test whether 16S rRNA, amoA and nxrB gene copies were correlated over time. Kruskal-Wallis rank sum tests were performed in the R basic statistics package ( R Core Team, 2014 ) to test whether the populations of the above genes were stratified by depth. VEGAN's ADONIS function was used on the V4-V5 depth dataset to test the significance of the observed Bray-Curtis dissimilarity as a function of the categorical factors of depth, with strata = ZERO because the same biofilter was sampled multiple times.

Biomass model

To determine whether the observed ammonia removal could provide the energy required to support the number of potential ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms (AOM) in the biofilter as quantified via qPCR, we included the steady-state biomass concentration from the measured ammonia oxidation modeled by the following equation:

:

X AO is defined in previous models (Mußmann et al., 2011) as the biomass concentration of ammonia oxidizers in milligrams per liter, but in this study we converted to cells per wet gram of sand by finding the mean grams of sand per liter of water in Biofilter. Θ x is the mean cell residence time (MCRT) in days and was unknown for the system. Θ is the hydraulic residence time in days, which in this system is ~9.52 min or 0.0066 days. Y AO is the growth yield of ammonia oxidizers and b AO is the endogenous respiration constant of ammonia oxidizers, which were estimated to be 0.34 kg volatile suspended solids (VSS)/kg NH4 + -N and 0.15 d -1 by Mußmann et al. (2011) . Δ S NH 3 is the change in substrate ammonia concentration between inlet and outlet in mg/l. To calculate _ _ _ _ _ _ *C/μm 3 ( Mußmann et al., 2011 ) to relate the biovolume to endogenous respiration. The modeled biomass concentration was plotted against a range of potential MCRT for a RAS fluidized sand filter (Summerfelt, personal communication). The results of all amoA qPCR assays were combined to estimate total ammonia-oxidizing microorganism biomass in copy numbers per gram wet weight of sand. The modeled biomass was then compared to our AOM qPCR assay results. A commented R script for the model is available on GitHub ( https://github.com/rbartelme/BFprojectCode.git ).

NCBI sequence accession numbers

Bacterial V6, V4-V5, and archaeal V6-16S rRNA gene sequences generated in this study are available from the NCBI SRA (SRP076497; SRP076495; SRP076492). Partial gene sequences for amoA and nxrB are available through NCBI Genbank and have accession numbers KX024777–KX024822. Results Biofilter chemistry results RAS operational data were examined from the beginning of a yellow perch rearing cycle to approximately 6 months thereafter. The mean biofilter influent concentrations of ammonia and nitrite were 9.02 ± 4.76 and 1.69 ± 1.46 μM, respectively. Biofilter wastewater ammonia concentrations (3.84 ± 7.32 μM) remained within the toxicological limitations (

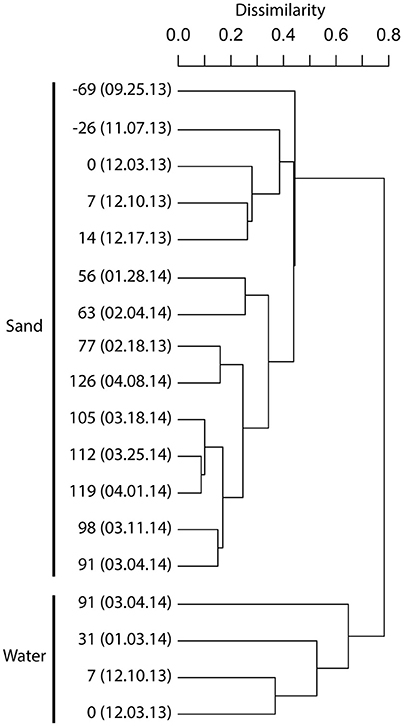

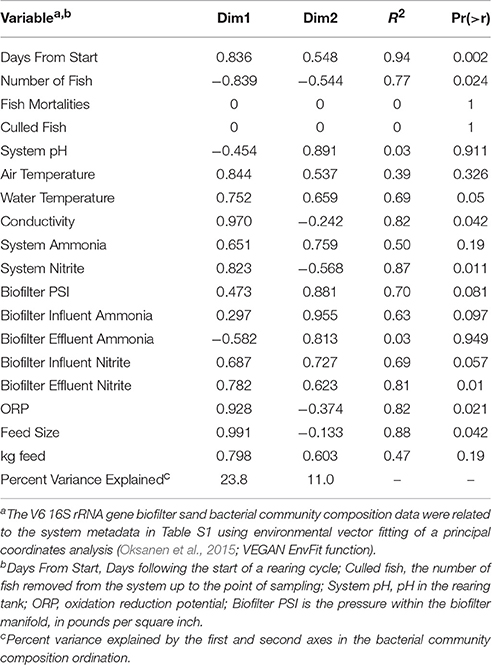

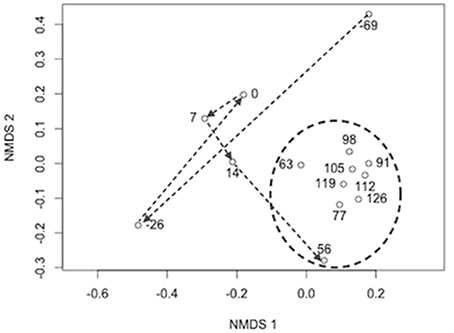

< 60 μM) of P. flavescens grown in the system. Occasionally, nitrite accumulated above the recommended threshold of 0.2 μM in both the rearing tank (0.43 ± 0.43 μM) and the biofilter effluent (0.73 ± 0.49 μM). No major fish diseases were reported during the RAS's operational period. Environmental and operational data are listed in Table S1. Bacteria and archaea accumulations within the biofilter Characterization of the RAS biofilter bacterial community showed that both the sand-associated and aquatic communities were diverse at a broad taxonomic level; Seventeen phyla averaged >0.1% in each of the biofilter sand and water bacterial communities (see Table S2 for an example taxonomic characterization of the genus). Proteobacteria (on average 40% of biofilter sand community sequences and 40% of water sequences) and Bacteroidetes (18% in sand, 33% in water) dominated both water and sand bacterial communities. In taxonomic classification at the family level, the community associated with biofilter sand was different from the aquatic community. The majority of sequences in the sand samples were assigned to the bacterial groups Chitinophagaceae (average relative abundance 12%), Acidobacteria family unknown (9%), Rhizobiales family unknown (6%), Nocardioidaceae (4%), Spartobacteria family unknown ( 4%) and Xanthomonadales - family unknown (4%). Water samples were dominated by sequences classified as Chitinophagaceae (14%), Cytophagaceae (8%), Neisseriaceae (8%), and Flavobacteriaceae (7%). At the genus level , Kribbella, Chthoniobacter, Niabella, and Chitinophaga were the most numerous taxa classified, each with an average of >3% relative abundance in the biofilter samples. Using Minimum Entropy Decomposition (MED) to obtain highly discriminatory sequence classification, we identified 1261 nodes (OTUs) in the entire bacterial dataset. A MED-based comparison of bacterial community composition (Figure 1 ) supported the patterns observed using a broader taxonomic classification, indicating that the biofilter sand-associated community was distinct from the assemblage present in the biofilter water. In contrast to the high diversity in the bacterial community, we found that the archaeal community is dominated by a single taxonomic group belonging to the genus Nitrososphaera This taxon accounted for >99.9% of the Archaea -classified sequences identified in the biofilter samples (Table S2). This taxon was also almost entirely represented by a single sequence (>95% of sequences classified as Archaea ) that was identical to a number of Thaumarchaeota sequences deposited in the database, including the complete genome of Candidatus Nitrosocosmicus oleophilus (CP012850), together with clones from activated sewage sludge, wastewater treatment and freshwater aquariums (KR233006, KP027212, KJ810532–KJ810533). Initial characterization of the biofilter community composition revealed distinct communities between the biofilter sand and decanted biofilter water (Figure 2 ). Based on these data and the fact that fluidized bed biofilter nitrification occurs primarily in particle-bound biofilms ( Schreier et al., 2010 ), we focused our further analyzes on the biofilter sand matrix. In the sand samples, we observed a significant change in bacterial community composition (MED nodes) over time (Table 2 ). The early part of the study, which included a period when market size yellow perch were present in the system (sample −69 and −26), a fallow period after fish removal (sample 0), and the period after restocking of mixed juveniles (Samples 7 and 14) had a more variable bacterial community composition (mean Bray-Curtis similarity 65.2 ± 6.5%) than the remaining samples ( n = 9), which were collected at time points after an adult food source had been started (20.0 ± 6.4%, Figure 3 ). Several operational and measured physical and chemical parameters, including oxidation-reduction potential, feed size, conductivity, and nitrite from the biofilter, were correlated ( S < 0.05) with the time-dependent changes in bacterial community composition (see Table 2 for environmental correlation results).

.

|

FIGURE 2. DENDROGRAM ILLUSTRATING THE BACTERIAL COMMUNITY COMPOSITIONAL RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN BIOFILTER SAND AND BIOFILTER WATER SAMPLES. A complete linkage dendrogram is represented using Bray-Curtis sample dissimilarity relationships based on nodal distributions of minimum entropy decomposition between samples (V6 dataset). The leaves of the dendrogram are labeled with the day count, with 0 representing the start of a fish rearing cycle. Negative numbers are days before a new breeding cycle. The day count is followed by the date of sampling (MM.DD.YY). See Table S1 for example metadata. |

|

TABLE 2. CORRELATIONS BETWEEN ENVIRONMENTAL VARIABLES AND BACTERIAL COMMUNITY COMPOSITION. |

|

FIGURE 3. NON-METRIC MULTIDIMENSIONAL SCALING DIAGRAM OF BRAY-CURTIS BACTERIAL COMMUNITY COMPOSITION DISsimilarity BETWEEN SAMPLING POINTS. nMDS stress = 0.07 and dimensions (k) = 2. Arrows show the progression of the sample through time from the end of a rearing cycle (day number -69 and -26) to a period without fish (0) and into the subsequent rearing cycle ( 7-126). The circle shows samples taken after the fish had grown to a size where feed type and amount were stabilized (3 mm pelleted feed and 3-7 kg feed per day). |

| Using a second sequence data set (V4-V5 16S rRNA gene sequences), we examined sand-associated bacterial community composition across a depth gradient (surface, middle, bottom). We found that the bacterial communities in the top sand samples were different from those in the middle and bottom (ADONIS R 2 = 0.74, p = 0.001; Figure 4 ). The planctomycetes represented a larger proportion of the community in the surface sand (on average 15.6% of the surface sand versus 9.6% of the middle/lower sand), while the middle and lower layers harbored a larger proportion of Chitinophagaceae (7.4% in the surface sand vs. 16.8% middle/bottom) and Sphingomonadaceae (2.4% in the surface vs. 7.9% in the middle/bottom; Figure 4 ). | |

|

FIGURE 4. DEPTH COMPARISON OF BACTERIAL BIOFILTER COMMUNITY COMPOSITION. A heatmap is presented for all bacterial families with a relative abundance of ≥ 1% in each sample. Relative taxon abundance was generated from V4–V5 16S rRNA gene sequencing and is presented on a scale of 0 to 25%. The dendrogram represents the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity between sample community composition. Sample IDs are listed and sample depth is indicated by on the graph next to the dendrogram. Sample names correspond to sample metadata in Table S1. |

Nitrification community composition and phylogeny

Context:

- Category: Biologie

-

Also available:

RSS

RSS